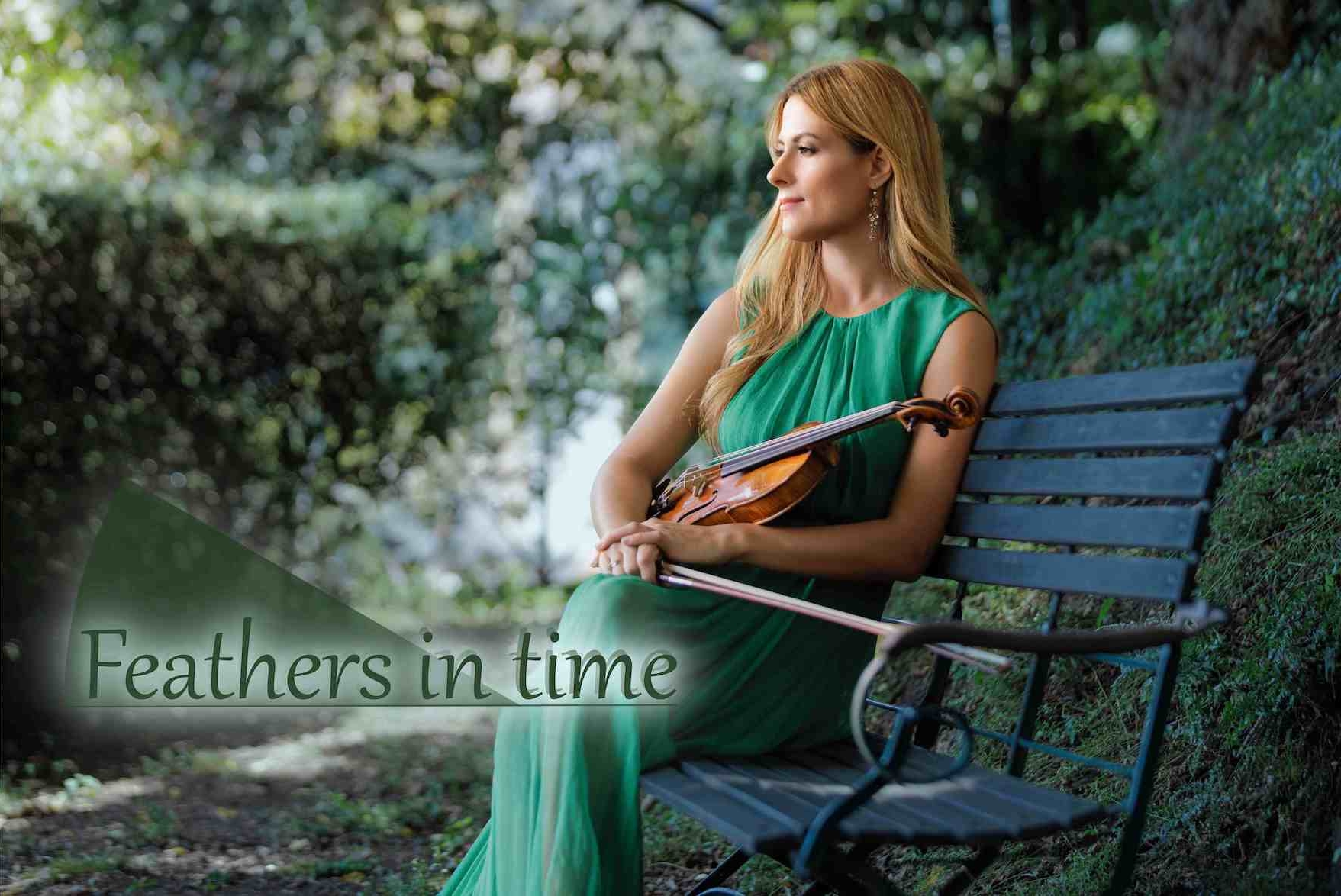

The most personal project of Francesca Dego’s career to date.

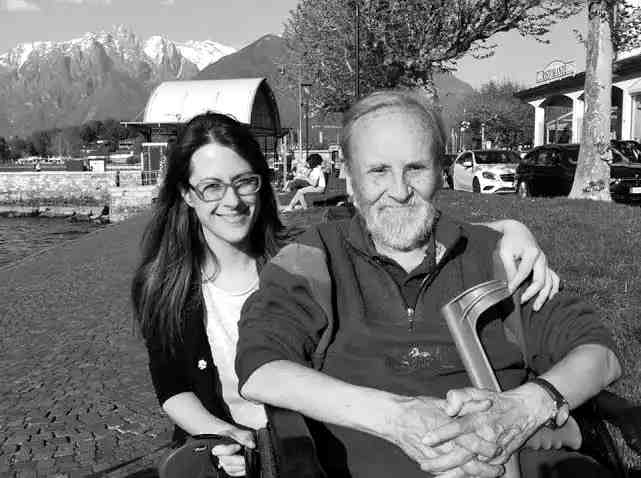

In 2020, Giuliano Dego—her father—passed away. He was among the most celebrated poets and writers of the second half of the Italian twentieth century, admired by figures such as Montale, Fellini, Calvino, and Quasimodo, the latter dedicating to him his final essay: the introduction to Dego’s poetry collection Solo l’ironia.

Giuliano Dego’s final poetry collection, published and distributed by Ladolfi Editore, is titled Piume nel tempo (Feathers in Time). It is a representative and captivating potpourri of published and unpublished works, where almost aphoristic rhymes alternate with poems of epic breadth.

For a long time, Francesca reflected on how best to honor and remember him. The answer that came from the heart was to unite their lives and passions—music and poetry—by inviting ten of today’s leading Italian composers to draw inspiration from his poems and write new works for solo violin. These pieces will be collected and performed by her around the world as part of the project Feathers in Time (Piume nel tempo).

She knows he would have appreciated this project, delving deeply into the language of each composer and losing himself in the many different interpretations of his own verses. She knows he is proud of her.

The project officially begun in December 2025, with a concert in L’Aquila for the Società Barattelli, featuring the beautiful piece Gli occhi di Giulia by Francesco Antonioni. It will then continue this season in Japan with the world premieres of works by Nicola Campogrande and Carlo Boccadoro, and in Pavia in February with music by Cristian Carrara.

“My father was my biggest source of inspiration growing up, and the one who put a little violin into my hands so this project is especially close to my heart and I hope it will also have an impact as I have never really commissioned new works extensively.”

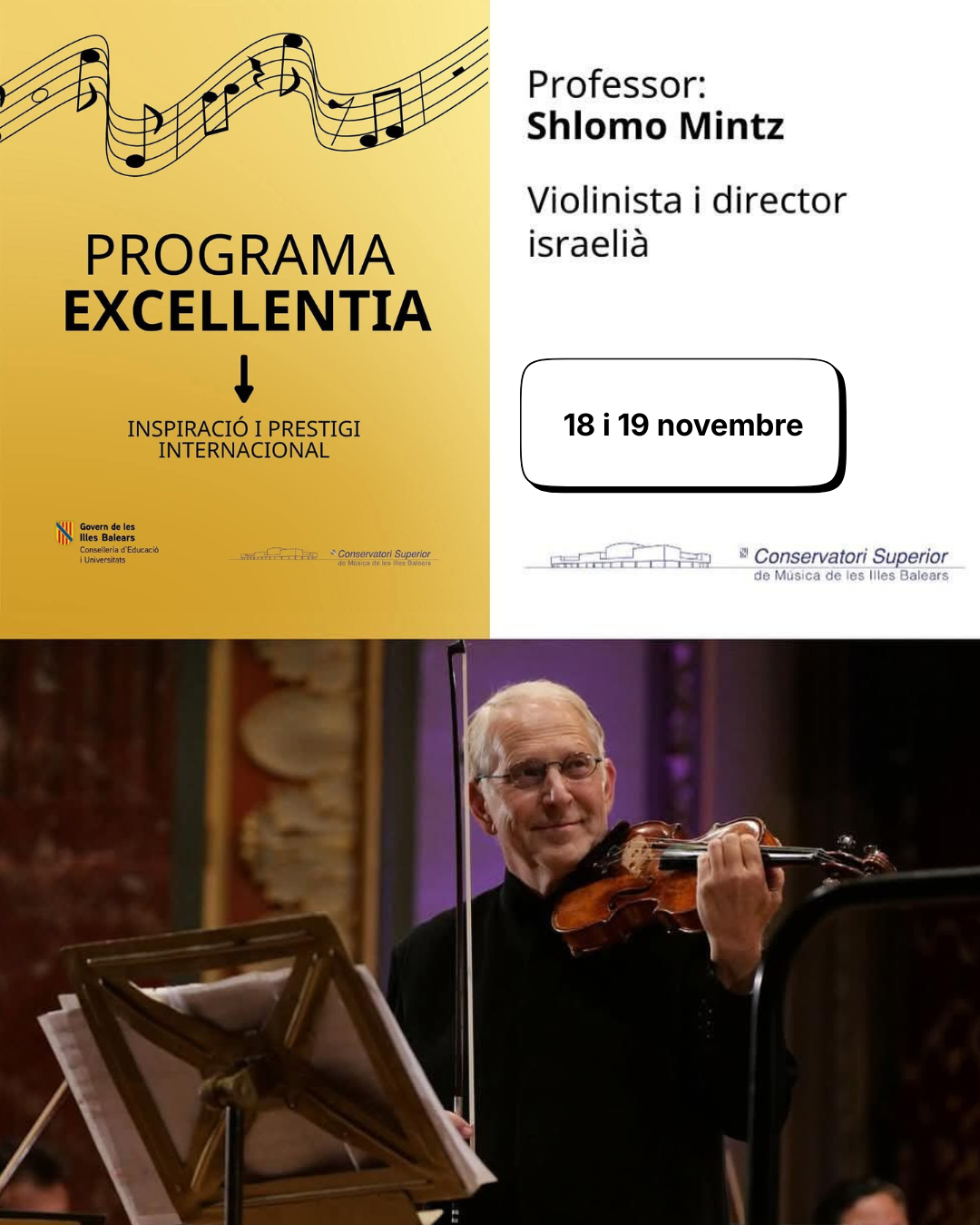

COMPOSERS: Silvia Colasanti “Dachau”, Nicola Campogrande “Il Poeta”, Carlo Boccadoro “Virtuale”, Giovanni Sollima “È solo un rito”, Cristian Carrara “Per Francesca”, Francesco Antonioni “Gli occhi di Giulia”, Daniela Terranova “Francesca”, Fabio Vacchi Octaves from “La Storia in Rima”, Virginia Guastella London Bridge

- Poems translated into English by the British poet Simon Barraclough.

At Dachau the wind

transports

to infinite rest

flint, quartz, grit,

commingled

with cinders

of what were men.

But the memory

will not shift

of these predators of pedigree

whose shadow

falls still

upon these scraps,

these brutal facts

that must be faced,

which is to say

the human race.

Eleven years old, my daughter,

and you weep for the Holocaust.

Beyond your mother’s wailing wall

life lives on, whispering,

“Think about what is just,

feel what is beautiful,

choose what is good.”

This way, among Wolves,

is the true way to honour

even the Lambs of the earth.

When books themselves

are obsolete,

who can say

if fruits and flowers

will cling to the colours

we painted with

humble words.

He says ‘What are you doing,

moving your fingers

in time with your feet?”

“I’m counting up syllables,

my friend, paid for

with my life.”

I wonder, though I would not steal from Mars

an ounce of fame, if all the tales we heard

in class, of purple hearts and silver stars

were worth the pounds of flesh, the youths interred.

The child prodigy

lays into Mozart,

bow blazing

with the light

of weightless years.

In a café near London Bridge

lovers meet at evening,

stroll along the Thames

on dream-blue pavements,

shadowed, perhaps, by fog,

or by the wind alone.

Is there really much more to say,

if I link my laughter to your language

and the cloud of fragile breath

on the window where you reach out

to write my name? Timeless intimate,

antique angel, it’s just a ritual of the ego,

tempered by the leaping of my heart

whereas, perhaps, for you,

heels and jigs fly and dart about.

But it is only a shudder,

its arabesques and dervishes

wheeling, exposed, as vulnerable

as sex, the only sign that we, here,

live not in tormented climes.